|

|

| Feedback |

|---|

Real Resources Review: A little makes a lot?I sent John Busby's 7th August article to a friend who understands more about nuclear power than I do. His reaction was that 'Mr Busby is not conversant with the concept of pebble bed reactors'. I would like to ask Mr Busby how he views that technology and whether he would care to tackle it in an article for the uninitiated like myself? Kind regards, Paddy Imhof

The problem is that mining of uranium is running down, whatever form of reactor is envisaged. See Die Welt which reports the imminent closure of some of the French reactors due to fuel shortages. The thorium alternative and fast breeders are dependent on vast development programmes which with the rapid and progressive failure of the nuclear industry will never be funded. As far as the pebble bed reactor is concerned it depends on the integrity of the pebbles and as these contain graphite this is likely to lead to the demise of this technology. The seven UK AGR's are likely to close prematurely as the graphite moderator blocks are disintegrating due to the irradiation which causes structural breakdown. Also there is an overheating due to the Wigner Energy effect which leaves a residual heat in the graphite. The gas-cooled fast reactor is also an unlikely candidate for funding for this reason as it relies on graphite moderation. The nuclear lobby in desperation is arguing that uranium can be extracted from the earth's crust and seawater and looks to fast breeders to generate ever more plutonium. All of which is fantasy. We do not have to wait too long for some of the

lights to go out in France, which will hopefully lead to a reality

check! |

| Economic Growth: Technological progress or stealing from the bank? |  |

|

| By Jon Rynn | |

| Apr/10/2007 | |

|

The Grand IllusionAs usual, mainstream economics only muddies the picture.[1] Despite what most people are led to believe, for all intents and purposes, neoclassical economics has no theory of economic growth[2] Robert Solow received a Nobel Prize in Economics for explaining economic growth, but his theory actually explains why technological change is responsible for most economic growth,[3] and since neoclassical economics cannot explain technological change, well, how embarrassing! The main problem for neoclassical economists in attempting to explain growth is that the basic theory used for explaining changes in production is an explanation of the decline of production, called the theory of diminishing returns. It is impossible to explain how something grows if all you have is a theory explaining how something decreases. The reason economists stick with the principle of diminishing returns is that this principle allows them to tell a story about how prices are determined, not how economic growth happens; and it allows economists to advance the fairy tale that people receive the wages and salaries commensurate with what they contribute to national wealth.

Back in 1899, the eminent economist John Bates Clark, along with his colleagues, was facing the problem of beating back the claim by Karl Marx and others that in a good society, each person should receive income according to their needs, or at the very least, according to their contribution to society. Clark solved this problem by asserting that every person already receives that which they contribute.[4] Today, when CEO's make hundreds of times the annual salary of most of their workers, the heirs to John Bates Clark's theory use this line of defense. But Clark’s idea, called marginal productivity, which undergirds the theory of economic growth as well, is the result of carrying what initially seems a reasonable mental exercise to absurd lengths. The theory of diminishing returns (and marginal productivity) is an example of arguing by using only a part of an analogy. , the inventor of the principle of diminishing returns, used the cutting edge of ecological theory of the time and noted that when one "factor of production" -- in his case, land -- is held constant, and another "factor of production" – labor -- is expanded, the addition of more labor leads to smaller and smaller additions to total output. Similarly, in an ecosystem, if one has, say, a prairie, and one adds, for instance, more and more deer, eventually the deer will have less and less grass for each deer. Ricardo's rival in economic thought at the time, Thomas Malthus, was making a name for himself by emphasizing the possibility that humans were like deer and feeding the poor would soon lead to a massive die-off of the population.

Ricardo, instead of using the analogy of the ecosystem in order to understand more about production in an economy,[5] simply stopped at this one mechanism of diminishing returns. The reason his principle works well for determining price is exactly because each additional person's contribution is diminishing , so that at some point, the cost to the entrepreneur/capitalist of hiring an additional person just equals the contribution that the additional person makes to the enterprise. The entrepreneur stops hiring, everybody receives a salary or wage that is pretty close to this final “contribution”, the CEO can claim that he/she receives compensation in the same way, and economists can maintain that we live in the best of all possible worlds. No there thereBut that leaves the sticky problem of economic growth.

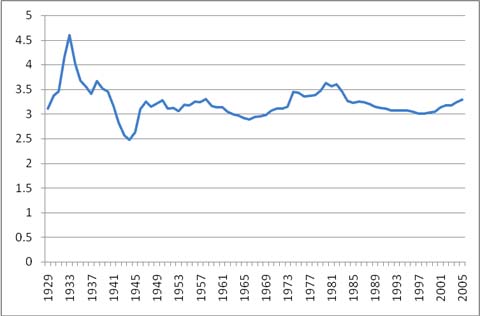

Historically, labor has received about two-thirds to three-quarters

of the national revenue, and capital the rest. So according to the

theory, labor must be contributing two-thirds to three-quarters of

the wealth. When growth occurs, then, it must be the case that labor

accounts for this same fraction, that the amount of time that people

work has increased by enough to account for growth. But over the

past century, even though the GDP has increased about 13 times from

1929-2005,[6] the total number of hours

worked in the U.S. has remained fairly constant. On the other hand,

the amount of capital fixed assets has gone up almost nine times.[7] In fact, total capital

assets have pretty much tracked total GDP; in econo-speak, the

capital-output ratio has remained pretty constant. But since labor's

"contribution" is much larger than capital's, capital should not be

the determining factor in growth, even though it certainly looks

that way. U.S. capital to output ratio, 1929-2005[8]

As the dean of American economists, Paul Samuelson, notes about this paradox, "A steady profit rate [that is, share of capital in national income] and a steady capital-output ratio are incompatible with the more basic law of diminishing returns under deepening of capital. We are forced, therefore, to introduce technical innovations into our statical neoclassical analysis to explain these dynamic facts".[9] Notice that since the law of diminishing returns is "more basic" than reality, reality is jettisoned, the use of the law of diminishing returns in calculating economic growth is retained, and a deus ex machina, called technological innovation, is "introduced". Thus was neoclassical economics a part of a faith-based ideology long before George W. Bush had even stopped drinking. Neoclassical economics cannot handle the concept of capital, and thus it cannot explain economic growth. However, conservative politicians still use the term "economic growth" in order to justify "free market" policies, not because they are relying on a neoclassical theory of growth, but because they are retreating to the even “more basic” principle of short-term economic models, that everybody’s welfare is maximized if the market is perfectly “free”. Within the international economy, Bill Clinton and other conservatives use the concept of free trade as a proxy for economic growth; the theory of free trade is basically an extension of the short-term model of a competitive market. Every time you hear a policy justified by the term “economic growth”, remember that there is no there there. Redefining progressThe only substantive use of the term “economic growth” is as a measure of the flow of goods and services in an economy, compared from year to year. Thus economists are relieved of the responsibility of accounting for the capital that creates those goods and services. In other words, even if flows have increased because people have been robbing banks, ecological or industrial, it looks like the economy is expanding. In order to begin to construct a useful concept of economic growth, we need to first establish a better way to measure it. We should be measuring the capital, or assets, that is, the wealth-generating components of the economy, not the flow of goods and services, as an indicator of economy-wide wealth.[10] The emphasis on flows was developed during the Great Depression, because Keynes pointed out that sometimes an economy gets stuck at a low level because the flows tail off, even if the capital/wealth-producing base is doing just fine. But now we have a different problem.

The central exhibit in this orgy of capital consumption has been fossil fuels, which accumulated over millions of years and will have been used up at the end of a couple of centuries. The only way to use fossil fuels sustainably would be to use them to create a renewable energy infrastructure of wind, solar, geothermal, and hydro power, a pile of capital that would replace the pools of oil, mountains of coal, and caverns of natural gas as the components of the energy infrastructure. We should be measuring growth by measuring the increase in wealth-generating capital from year to year, perhaps replacing GDP with Gross Domestic Capital. If a factory is constructed, growth increases; if oil is used, wealth has declined. If soil is added to an area, wealth grows; if soil blows away, we are poorer. We could even extend this concept to people, perhaps in a separate gross domestic human capital index: when people become healthier, wealth goes up, when they become sick or injured or die, wealth goes down. When people get an education, or spend more time in a skilled job, wealth goes up; when they are fired and can't find work or find lower skilled work, wealth goes down. Controlled GrowthHowever, the problem of growth is not simply the problem of counting the wrong phenomena. We should set up democratic social structures that will help natural, human, and machinery capital to bloom. We need a way to change power and ownership in the society. Two ways of doing so are to encourage employee ownership and control, and public ownership and control. Employee ownership and control would give power to people who live in the vicinity of the firm. Because they live in a particular place, the people so empowered would seek to create economic wealth in a way that was compatible with the long-term sustainability of the resources and capital of their area. In addition, the goal of the firm would broaden from a single-minded devotion to maximum profit to the expansion of the decision-making power of the top executives of the firm. Thus, such firms might be able to ignore Marx's famous dictum that capitalists must accumulate or die, and they might avoid the worst of what Murray Bookchin called “uncontrollable growth”.[11] In a firm in which the employees are in control, the greatest imperative is the long-term health and well-being of the company. Public ownership and control, preferably at the local level, would also push the economic system toward a sustainable course, as long as government officials could not profit in any way from public control. After all, the land, soil, forests, rivers and flora and fauna on the soil, and the resources below it, are the common resources of humanity that are needed for survival. New Orleans and Louisiana are examples of areas that have not reaped the rewards of the oil and gas in their territories. When ownership of land leads to power, as it usually does, it also leads to concentration of power in a positive-feedback loop that often ends in tyranny. The nature of public control of the economy has been debated for centuries, with neoclassical economics forming the basis of the conservative assault on government. But governments have always controlled much of the physical infrastructure, and have also generally planned the changes in urban structure – thus the term, “urban planning”. When a local government creates a viable downtown, it encourages sustainable economic growth; when, in concert with the Federal government and oil and car companies and real estate interests they create suburban sprawl, they set up the conditions for parasitic growth. New and ImprovedThe concept of economic growth can rest on a measure of wealth-generating capital, and can be encouraged by democratizing control of the economy. We also need to differentiate between parasitic growth, based on quantity, and sustainable growth, based on quality.

When growth is the result of improvements in machinery, or the organization of work, or the improvement in public spaces or infrastructure, such growth is the result of an increase in quality. Certain categories of machinery, which I have called reproduction machinery, are capable of collectively creating more of themselves, and are also responsible for creating the various kinds of machinery that, in turn, create the goods and services that constitute the flows of the economy. For example, machine tools create the metal parts that make more machine tools, steel-making machinery creates the steel to make machine tools and more steel-making machinery, and machine tools are used to help make the steel mills. When technological improvements are made in these types of machinery, whole new eras may result.

The constant improvements in semiconductor-making machinery, for instance, have led to the computer and internet revolutions, as well as to better designed machinery of all sorts. In the natural world, as Malthus, then Darwin, and many others have remarked, the explosive nature of reproduction leads to growth. Humans have devised reproduction machinery to accomplish economic growth. These machines can be turned to the task of making more quantity, or they can be used to create better quality. As the fossil fuel era comes to a close, the blind pursuit of quantity will have to be replaced with a greater emphasis on quality as the road to growth. It might seem that a focus on machinery would dehumanize society, but exactly the opposite is true. Machinery cannot design itself, maintain itself, or fix itself; machinery needs help building itself, managerial pipe dreams notwithstanding. In order to shift to a quality-centered economy, the national work force will have to be given the mental, physical, and financial tools needed to turn themselves into a highly skilled workforce. Ironically, by emphasizing labor instead of capital, neoclassical economists treat labor as a commodity, made up of unskilled, substitutable components. By taking capital seriously, we see that labor is not an undifferentiated mass, but the basis of sustainable economic growth. The rise of industry has been propelled by the coevolution of both quantity and quality-led economic growth. Even the loss of fossil fuels would not necessarily bring us back to a preindustrial society. We have the accumulated wisdom of centuries of experience with machine tools, semiconductor making machinery, electricity-generating turbines, metal-making machinery, and much more; using these tools, we can radically reduce the human footprint on the Earth while allowing for life, liberty, and maybe even the pursuit of happiness.

[1] For an example of the latter, see Bill McKibben’s most recent book, Deep Economy . [2] For a more in-depth analysis, see my critique of neoclassical growth theory, a chapter from my political science dissertation, at the following link . [3] For instance, see Robert Solow, 1994. “Perspectives on Growth Theory,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 8 (Winter): 45-54, which acknowledges “a criticism of the neoclassical model: it is a theory of growth that leaves the main factor in economic growth unexplained”. [4] Clark, John Bates. 1927. The Distribution of Wealth: A Theory of Wages, Interest and Profits. New York: MacMillan Company. [5] For an attempt to use

ecosystems as an analogy for an economy, see my article “The

Economicy is an Ecosystem”, at the following link

. [6] From Statistical Abstract of the United States, table 648, “Gross Domestic Product in Current and Real (2000) Dollars”, Constant 2000 dollars. [7] See “Table 1.2.

Chain-Type Quantity Indexes for Net Stock of Fixed Assets and

Consumer Durable Goods” at the Bureau of Economic Analysis website,

at the following link

. [8] Capital data taken from

the Bureau of Economic Analysis website, “Table 1.1. Current-Cost

Net Stock of Fixed Assets and Consumer Durable Goods”, at the

following link

. GDP data taken from Statistical Abstract of the United States,

table 648, “Gross Domestic Product in Current and Real (2000)

Dollars”, excel format, Historical Data worksheet, at the following

link.

[9] Samuelson, Paul. 1975. Economics . New York:McGraw-Hill, p. 747. [10] The seminal work in calculating a sustainable measure of GDP is by the organization Redefining Progress, at http://www.rprogress.org/ , although they mix both flows and assets in their accounting. [11] Murray Bookchin. 1989. Death of a Small Planet. The Progressive (August): 19-23, available at the following link. I would like to thank Colin Wright for point out this article to me. |

|

| Register Free to receive updates of latest stories |

|---|

| Polls |

|---|

The

concept of economic growth is used to advance various agendas,

sometimes as an excuse for conservative economic policies, sometimes

as an argument to consume less. The term "economic growth" can be

useful, but only if one properly defines what it is that is growing.

When people become richer because they steal from a bank, one

shouldn’t add the thieves' riches to the gross domestic product.

When resources like soil, forests or oil are used up , the

GDP allegedly goes up. On the other hand, when a

computer the size of a room can fit into a small briefcase, this

shrinkage can also be called growth. How can we construct a more

useful concept of economic growth?

The

concept of economic growth is used to advance various agendas,

sometimes as an excuse for conservative economic policies, sometimes

as an argument to consume less. The term "economic growth" can be

useful, but only if one properly defines what it is that is growing.

When people become richer because they steal from a bank, one

shouldn’t add the thieves' riches to the gross domestic product.

When resources like soil, forests or oil are used up , the

GDP allegedly goes up. On the other hand, when a

computer the size of a room can fit into a small briefcase, this

shrinkage can also be called growth. How can we construct a more

useful concept of economic growth?